What is God’s name?

Recently, a debate has erupted amongst Bible scholars over how to pronounce God’s name in the Bible.

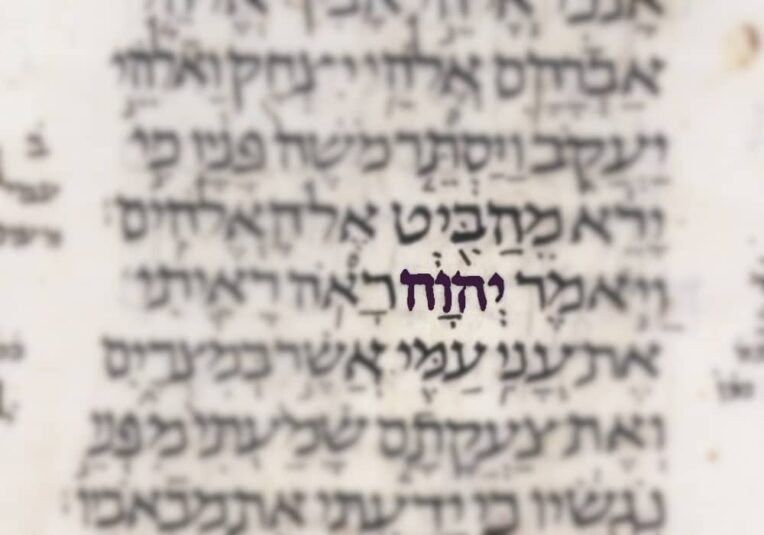

In the ancient Hebrew language, God’s name is presented as a four-letter word known as the “Tetragrammaton,” יהוה. In English, this is “YHWH.” It appears almost 7000 times in the Old Testament. The language didn’t have any written vowels. Jews from the period would pass down how each written word sounded verbally. This continued until the language ceased being used, largely due to Israel going into captivity in Babylon.

Sometime after they were taken to Babylon, the ancient Jews, for several reasons, stopped pronouncing God’s name. This led to the problem we have today. Since the pronunciation of words was totally reliant on the Jewish people verbalizing what they read from the Old Testament Scriptures, no one today truly knows how to pronounce God’s name.

God’s name in the New Testament

The New Testament, written in Greek, uses the Greek word meaning “Lord” when quoting the Old Testament verses containing the Tetragrammaton. Similarly, when the Old Testament was brought into the Greek language, the Tetragrammaton was translated into the word “Lord” as well since they didn’t know how to pronounce the actual word.

Eventually, translators started trying to figure out how the Tetragrammaton might have been pronounced. As the Greek was translated through the centuries, the pronunciation “Jehovah” became a popular way of transliterating the “YHWH” found in the manuscripts.

“Jehovah” was used in many bible translations that we’ve seen through the years, most of them choosing to leave the word “Lord” in its place. Newer research has started to lean towards another translation of the Tetragrammaton. Many modern scholars believe that a better translation of YHWH would be “Yahweh.”

The debate

And here lies the debate. “Jehovah” and “Yahweh” sound very different. Many go so far as to say that one or the other are actually false gods. I won’t bother repeating the rhetoric, a simple Google search will lead anyone down the rabbit hole if they wish. But the fact that there is so much tension between the two camps, one says that “Jehovah” is God, the other says it’s “Yahweh,” makes one wonder: since those are so different, which one is correct? What is God’s name?

How we forgot God’s name

The first time the Tetragrammaton is used in the Old Testament is found in Genesis 2:4. In this verse, it’s presented in what seems like a normal fashion: with the name (the Tetragrammaton) before the title “God.” It’s used several times after that in the same chapter, setting up the foundation for the LORD’s ownership and authority over his creation. The fact that this is thrown in there without introduction is interesting and suggests that the readers would have been familiar with who exactly God is when this was written.

Their familiarity with God’s name was likely due to them having heard the name due to it being passed down to them through their generations or from the teaching of Moses, who is believed by many to have written these scriptures.

God introduces himself

In Exodus 3:15, Moses is told by God that his name is YHWH. Verse 14 provides extra details about the name’s meaning as “I am who/what/that I am.”1 This name is significant for several reasons. It speaks to the nature of God as one who is, or one who has being. In contrast to the gods of the surrounding people, “the LORD (YHWH) God of [Israel’s] fathers” exists in the sense that he just is, rather than having been created. YHWH is self-sustaining and has authority over his creation and over the kingdoms of man.

The Jews wanted to protect God’s name

With time, the Jews started to not pronounce the name, instead opting to use the Hebrew word “Adonai,” which means “Lord.” There are thought to be several reasons for this.

The first is that they were concerned with misusing it, and thus violating the commandment to “not use the LORD’s name in vain.”

Another reason they could have prohibited its use would have been to preserve its sanctity and prevent its misuse by other people groups in the region, who had a practice of invoking the names of other people’s gods in their cursing and insults. The Jews limited its use, at some point after the Babylonian captivity, solely for the traditions and services of the priests in the Temple2.

This lack of common usage by the people eventually led to only a few knowing how to pronounce YHWH. This was exasperated by the fact that their language didn’t have any written vowels. So they couldn’t simply look at how it was spelled to learn it again.

A New Testament tradition

Once the New Testament authors came along, most people, including these authors, quoted the Old Testament verses with the Tetragrammaton using the Greek version of the word “Lord.” They kept using “Lord” instead of God’s name, which has led to a tradition of many translators today doing the same thing.

Many say we should continue with this tradition. They often cite the same reasons as the ancient Jews did: the name is special, so we don’t want to mispronounce or misuse it; or, the Apostles, even under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, didn’t translate it as a name, they used the word “LORD” instead, so we should do the same.

Others say they want to have a translation that accurately shows the original words. “The LORD” is not original to the text, so they work to try to figure out how it would be pronounced.

Why God’s name translated as “Jehovah?”

The Roman Empire, which was the home of early Christianity, spoke in Latin. Latin doesn’t have the letter “Y” in it, and the closest thing to it would be the “I” or, more likely, its variant the “J,” which made the “Y” sound like in the word “yes.” Latin also doesn’t have a “W,” instead the “V,” which could also be written as a “U,” would have been used. When Latin translators worked on the Tetragrammaton, in their transliteration of the letters they used JHVH.3

Reviving a dead language

As stated earlier, the ancient Hebrew language had no written vowels. This became a problem as the language began to die, anyone looking at the Hebrew writing couldn’t read it very well. The Masorites, who were Jewish scholars and scribes in the 5th through the 10th centuries AD, worked on reconstructing the Hebrew language. They added vowel symbols to the letters so those reading the Hebrew could sound out the words.

In their process, they added the vowels of the Hebrew word “Adonai,” which means “Lord,” to the letters of the Tetragrammaton to remind the readers that “Adonai” was to be used in its place.4

At some point in the Middle Ages, translators began to interject the vowels from the Hebrew word “Adonai” into the Latin transliteration of the Tetragrammaton of “JHVH.” This gave us the name which in Latin would have been pronounced something like “Yahowah.”5

Latin began to spread and other languages sprang out of it in Europe. The Latin letters took on the new sounds of the local languages producing what we know today in English as “Jehovah.”

Why do they now translate God’s name as “Yahweh?”

From here, scholars merely had to work backward. Now they conclude that “Yahweh” would be a better pronunciation. The evidence we currently have is that there was no “J” sound in Ancient Hebrew. The “V” sound is still being debated and most scholars think that it was pronounced more like a “W” in ancient times.

On top of that, there are plenty of names of places and people in the Old Testament that contain the “YH” of the divine name which are pronounced with a “yah” sound, such as Jeremiah(יִרְמְיָה), Josiah (יֹאשִׁיָּה), and also the Hebrew word “Hallelujah” the “jah” is pronounced as “yah.”

There are also some early Greek manuscripts that speak about how the Tetragrammaton would have been transliterated into Greek. These manuscripts use the transliterations “ἰὰ οὐὲ”6 (“Iaowe”)or “Ἰαῶ”7 (“Iaoh”)which would read similar to “Yahweh.”

The basic argument that those translating it this way tend to use is that, since this is a proper noun, a name, then we should seek to translate it as close to how it would have been pronounced in the original language, which most scholars agree would be “Yahweh.”

This is a relatively new understanding. There are only a couple of modern translations of the English Bible that have decided to translate the Tetragrammaton as “Yahweh” instead of keeping with the tradition of “Jehovah” or “the LORD.”

So which is Better? “Jehovah” or “Yahweh?”

Those who translated the Tetragrammaton as “Jehovah” did so with the best information they had at the time. They did it in an effort to accurately represent the word in our language. We are discovering new things about ancient languages all the time. Inevitably, our understanding of how an ancient word could have been spoken will change.

At this time, the evidence seems to indicate that the English “J” sound in “Jehovah” came into being through the natural process of English’s separation from the other languages in Europe. Many scholars believe that the “V” sound was also not original to the ancient Hebrew language.

“YH” is not always translated as “Yah” in Biblical names

There are also a lot of other names in the Bible that contain the “YH” from the Tetragrammaton. When brought into English, they have a “Jah” or “Jeh” sound. One of them is Elijah, which translates as “God is [the LORD],” or “God is Jah.”

Most notably of all the names in the Bible containing the first half of the Tetragrammaton is the name “Jesus.”

In Hebrew, “Yeshua” would have been Jesus’ name. In Greek, it’s translated as “Iesous.” You’ll notice that the first two letters in “Iesous” match the first two letters in “ἰὰ οὐὲ” from the Greek transliteration of “YHWH” above. When Latin speakers translated this, they replaced the “Ie” sound with a “J,” which as stated earlier made the “Y” sound in Latin which led to other languages pronouncing it with the “J” sound later like we do in English. He was NEVER known as “Jesus” with the English “J” sound when he was alive. His friends, family, followers, and enemies would have all pronounced his name in Hebrew, Aramaic, or Greek.

Why stop at changing just one name?

All of this, and yet, with the exception of those in the Hebrew Roots movement, there doesn’t seem like much of an effort or desire to call him by his name as it would have been originally written.

So, if we are going to change some of the names in our English Bibles to reflect how they would have been pronounced at the time they were written, why would we not change all of them? We are going to strive to pronounce God’s old covenant name correctly, why not do the same for Jesus’ name?

It seems the only good answer to this is to accept that it comes down to how different languages change over time. Is “Yahweh” a better translation than “Jehovah?” Based on the evidence, it’s probably a little bit closer to how it was originally pronounced, but no one knows for certain, and the best we can do is a scholarly guess.

This is ok.

God knows that we don’t have all the information. We should trust that he will be gracious toward our best efforts to honor him. Considering that, whether we think “Jehovah” or “Yahweh” is correct shouldn’t matter.

BUT WAIT. There’s one good reason why God’s name should matter.

God’s name is important.

In Exodus, the name itself means something of significance, teaching us about his very nature as one who is, apart from all other things. It teaches us that he is eternal, from everlasting, self-sustaining. It differentiates him from the false gods which surround his people. He uses it as a firm foundation to swear by in confirming his covenant with his people.

Obviously, we should care about His name.

At the same time, he knows the importance of his own name. If God knows the significance of his name, and he has the ability to make it known to anyone he wants, then why would he allow it to be forgotten?

This article from “Theologyfirst.com” provides a very good Biblical explanation of why.

The loss of the true pronunciation of YHWH seems providential.

The Jews first started the practice of not pronouncing the Tetragrammaton around the same time they went into exile in Babylon.8 They likely had little to no knowledge of its pronunciation by the time Jesus was born around 600 years later.

At the same time, the Apostles who wrote the New Testament, under the inspiration of the Holy Spirit, quoted the Old Testament verses containing the Tetragrammaton as “the LORD.” If God’s name, YHWH, was supposed to continue in mainstream usage, surely they, and the Holy Spirit, would have included its use in the New Testament. To our knowledge, they didn’t, and there have since been 2000 years of mostly using “the LORD” instead.

God chooses to reveal his name to us

In the Old Testament, the LORD chose to reveal himself to Moses with his Old Covenant name of YHWH. But now, in the New Testament, we are given a new and better covenant by Jesus, the Son of God who IS also God. In fact, the name “Jesus,” containing the first two letters of the Tetragrammaton, means “The LORD Saves.” What’s interesting is that when the angel in the gospel of Matthew is telling Joseph to name the child in Mary’s womb “Jesus,” he says to name him Jesus because “he shall save his people.” The angel is saying that Jesus is the LORD by interpreting the name “The LORD saves” as “He will save…” referring to the child himself.

Honor was given to the name YHWH as God in the Old Testament, but in the New Testament, we see it taught that the name of Jesus is to be given the same honor as God. Many verses prove the deity of Christ, and there are many verses that quote the Old Testament passages about God and point to it being about Jesus.

Conclusion

It’s clear in the New Testament that Jesus is equal with God, and being equal, he is worthy of and given the same honor as God. As an equal in the trinity, the name of “Jesus” is on par with the name of “YHWH.” Even as an equal, Philippians 2:9-10 says that God “highly exalted him and gave him a name above every name.”

That’s why I conclude that “Jesus” is the name of God we should all be concerned with, rather than “Yahweh” or “Jehovah.”

We should be more concerned with the name of Jesus than both of those names for several reasons:

- “Jesus” not only contains the old covenant name for God, “YHWH,” but it conveys much more information. The name “Jesus” teaches the Gospel message, “The LORD saves,” this is the power of God unto salvation (Romans 1:16).

- The old covenant, which is passing away according to Hebrews 8:13, was given to us with the name, “YHWH,” the sound of which has been forgotten. But this new and better covenant we’re now in is established with the name of Jesus, the name above every other name, which we’ve all heard and know.

- It’s to the name of Jesus that every knee will bow. It’s Jesus Christ that every tongue will confess is Lord(Philippians 2:10-11).

What ever his old covenant name sounds like, how ever it gets translated, it is clear that in the new covenant, God’s name is Jesus.

Footnotes:

- Alter Robert (2018) The Hebrew Bible: A Translation with Commentary (Volume 3) W.W. Norton ISBN 978-0-393-29-2503 ↩︎

- Marlowe, Michael. “יהוה The Translation of the Tetragrammaton.” Bible-Researcher, Sept. 2011, www.bible-researcher.com/tetragrammaton.html. ↩︎

- “Is Jehovah the True Name of God?” GotQuestions.Org, God Questions Ministries, 12 May 2014, www.gotquestions.org/Jehovah.html. ↩︎

- “Yahweh.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 4 Mar. 2024, www.britannica.com/topic/Yahweh. ↩︎

- “The Anchor Bible Dictionary / 6, ‘Yahweh.’” Edited by David Noel Freedman et al., Internet Archive, New York : Doubleday, 1 Jan. 1992, archive.org/details/anchorbibledicti0006unse/page/1010/mode/2up. ↩︎

- Stromata v,6,34; see Karl Wilhelm Dindorf, ed. (1869). Clementis Alexandrini Opera (in Greek). Vol. III. Oxford: Clarendon Press. p. 27 ↩︎

- Origen, “In Joh.”, II, 1, in P.G., XIV, col. 105. Footnote says that the end of name Jeremiah is reference to the Tetragrammaton which the Greeks pronounce Ἰαώ ↩︎

- “Yahweh.” Encyclopædia Britannica, Encyclopædia Britannica, inc., 4 Mar. 2024, www.britannica.com/topic/Yahweh. ↩︎

Related articles:

New

Leave a Reply